The Huldah Gates

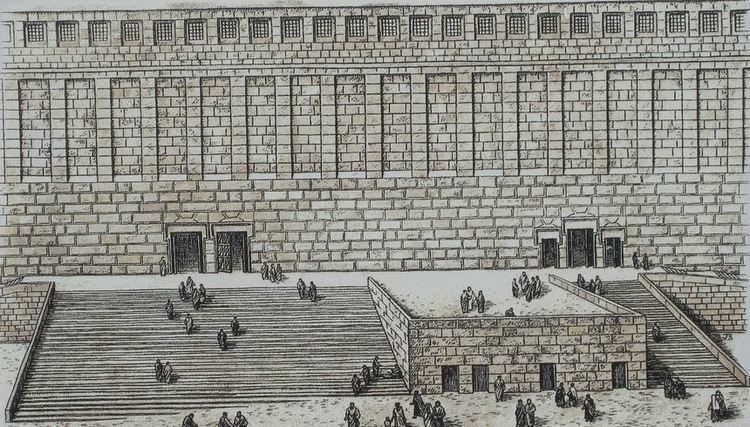

In Jerusalem, on the southern wall of the Temple Mount, stand the remains of two ancient gates. Today these gates are sealed, and archeologists simply call them the “Double Gate” and the “Triple Gate” on account of the number of arches they have. Yet anciently these gates were called the “Huldah Gates,” named for the prophetess Huldah whose story is told in the Hebrew Bible. According to the Mishnah the Huldah Gates were the most important entrance and exit used by Jewish pilgrims to enter the Temple Mount in the time of the second temple.[1]

The Western Huldah Gate, with its three triple arches, was used by pilgrims entering the temple mount, while the Eastern Huldah Gate, with the double arches, was used by pilgrims exiting the temple complex.[2] These gates connected directly to the temple mount and would have guided pilgrims through underground tunnels into the outer courtyard of the Jewish temple. Today visitors to Jerusalem can still see, and even walk on, the remains of the two monumental staircases that were attached to the Huldah Gates. These staircases, rising from the bottom of the valley up to the Huldah Gates, created an “ascent.” They were designed to create the feeling of “going up” to the Lord and leaving behind the profane for the sacred. It is estimated that during the important Jewish festival days, like Passover, hundreds of thousands of Jews would have ascended and descended the staircases and passed through the Huldah Gates on their way into and out of the temple.

Most of the other gates of Jerusalem in antiquity were descriptive of the activities that occurred around them such as: Dung Gate, through which the refuse of the city was brought and Water Gate where the water from the Gihon Spring entered the city. Even the gates named after animals were descriptive of the activities that involved them. For example, Sheep Gate was the gate through which the sacrificial lambs for the temple were brought, and Fish Gate was close to the part of the city where merchants sold fish. According to Jewish tradition the tomb of Huldah was within the vicinity of the gates, thus the name the “Huldah Gates” was descriptive of the area in which the gates were located. The Tosefta says that there were only two tombs in all of Jerusalem, that of King David and Huldah, which remained untouched from ancient times until antiquity.[3] As one scholar wrote,

“An old rabbinic text discusses this issue. It states: All tombs are evacuated [when a city expands to engulf them] except the tomb of the king and the tomb of the prophet. Rabbi Aqiva says: The tomb of the king and the tomb of the prophet are also evacuated. They said to him: But the tomb of the House of David and the tomb of Huldah the Prophetess that were found in Jerusalem were never disturbed (tBava Batra 1:11). This tradition mentions two well recognized tombs that were still to be seen in Jerusalem shortly before the Second Temple was destroyed. About one of them, the tomb of David, we also hear from Josephus (Ant 16:179-83). The other is, surprisingly, the tomb of the Prophetess Huldah.[4]“

While archaeologists have not yet found any remains of Huldah’s tomb, it is probable that her tomb may have stood in the area outside the Huldah Gates.[5] Baruch and Reich, archaeologists who excavated near the Temple Mount, wrote, “It should be remembered that the Temple Mount was considerably enlarged southward during the renovation initiated by King Herod. One possibility is that the gates, which were part of the southern Temple Mount wall from before the time of Herod, also moved southward at this time. The historical record sheds no light as to whether the name Huldah Gates refers only to the pair of gates that were part of the old Temple Mount (which is described in Middot) or whether the name of the old gates was transferred to the new ones.[6] While there is an alternative Jewish legend that says Huldah was buried on the Mount of Olives, it makes sense that– just like the other gates of the temple– the Huldah Gates would be descriptive of their location and be located near the remains of Huldah’s tomb. [7]

Yet no matter where Huldah’s tomb was, the reverence for Huldah’s burial place, and the subsequent naming of the main gates of the temple after her, indicates to us that she was held in high esteem by the ancient Jews and that her story was well known and revered. This is important because in modern times the story of Huldah has not always been greatly venerated. Throughout the 19th, 20th, and even into the 21st century Huldah’s story was routinely excluded from Jewish and Christian liturgical readings, teaching materials, Sunday School curriculums, children’s Bible readers, books on the Old Testament, and even in books that specifically focused on women in the Bible.[8] For example, in the 54 haftarah readings that are traditionally read in Jewish synagogues none of them include Huldah’s story, and while Christian churches regularly display images of prominent women from the Bible in their mosaics and artwork, Huldah is rarely portrayed.[9]

This is in contrast to the two other “prophetesses” in the Hebrew Bible, Miriam and Deborah, whose stories are included in the haftarah readings and whose images show up repeatedly in Christian churches all over the world. The stories of Miriam and Deborah are greatly revered by both Jews and Christians, and their stories are routinely shared with children and used in religious teachings. This disparity between Huldah’s story and that of the other prophetesses is evident even in the simple fact that the names Miriam and Deborah are common female baby names while the name Huldah has never been especially popular, even among Jews.[10]

This omission of Huldah may be because her story does not fit well within the confines of the roles and responsibilities that medieval and modern Judaism and Christianity have traditionally given women. Unlike the other prophetesses of the Hebrew Bible Huldah speaks authoritatively and her counsel and prophetic voice were sought out by the king in preference to that of the male prophets, even the venerable Jeremiah who was her contemporary. The preeminence of a woman prophet over a male prophet has made many rabbis and theologians throughout history uncomfortable. It is possible that Huldah was left out religious materials simply because modern Jews and Christians didn’t know quite what to make of her.

Which makes the fact that the most majestic and commonly used gates leading up to the Second Temple were named after Huldah, significant. It suggests that ancient Jews had a favorable view of Huldah, and that her role as a prophetess may not have posed the same theological or social complications as in medieval and modern times. It also helps us see that Jewish women of this time period may have had more freedom and opportunity within their religion than is traditionally thought. Examining Huldah’s story can give us insights into how Jews of the second temple period viewed women’s religious roles and spiritual gifts, and how the Huldah Gates might have influenced those perceptions.

The story of Huldah is told in 2 Kings 22 and 2 Chronicles 34 in which we learn that after the “book of the law” was discovered in the temple, King Josiah sent Hilkiah the priest and four other royal advisors to Huldah so that they could “enquire of the Lord… concerning the words of this book that is found.”[11] The text gives us three details about Huldah, first, that she was הַנְּבִיאָה “the prophetess,” second, that she the wife of a man named Shallum who was the שֹׁמֵר הַבְּגָדִים “keeper of the wardrobe,” and third, that she lived in Jerusalem in an area called the מִּשְׁנֶה “mishneh.”

The Prophetess

Huldah’s designation as a “the prophetess” may, by modern religious standards, be an unconventional role for a woman.[12] Yet, anciently the idea of a woman prophetess was nothing unusual. In fact, we know that in Mesopotamia prophetesses were much more common than prophets.[13] The majority of prophecies we have from Assyria and Babylon were given by women. Additionally, female prophets were highly revered in Greece and Rome. In fact, in Greece the highest source of spiritual guidance came from a woman, the oracle in Delphi. So, the idea that a woman could receive revelation from God and speak it authoritatively, was completely acceptable in the ancient world. It is even possible that naming the gates after Huldah was a socio-political maneuver by Herod, as a way to show the Romans that the Jews held similar beliefs as the Hellenistic world.[14]

There were other, well known male prophets actively teaching and prophesying within Jerusalem at the same time as Huldah. Jeremiah and the prophet Zephaniah were both prophets during the time of King Josiah and were known to have preached in Jerusalem. They were contemporaries of Huldah, and it is possible that both of them could have been in Jerusalem at the same time as her. Yet, Josiah’s ministers chose to consult Huldah rather than them. This is a situation that has made the medieval rabbis and Christian theologians uncomfortable, since their religious rhetoric prioritized male authority.

Rabbinical explanations for this oversight range from concluding that Jeremiah must not have been in town when they needed the scroll read, that Jeremiah and Huldah were cousins and therefore she gained her prophetic gift through him, that her prophetic gift was a reward for her husband’s piety, and the idea that Josiah specifically consulted Huldah instead of Jeremiah because he hoped a woman would respond more mercifully.[15] Christian theologians, such as St Jerome, explained that it was only because the men of Josiah’s time had gone astray that God consulted with a woman. For other theologians the idea that a woman could receive revelation from God, and that her word would be accepted by other men as definitive, was unsettling.

Yet amazingly, the Biblical author makes no attempt to explain why Huldah is called “the prophetess,” or why Josiah’s ministers consult her instead of a male prophet. The Biblical author seems to assume that the whole situation is self-explanatory and unremarkable. This nonchalant attitude towards Huldah’s position seems to indicate that to the ancient Jewish mind the situation of a woman prophesying, and declaring the word of God with authority, was not problematic. Huldah’s gender plays no part in her ability to communicate with God or speak in his name.

The inclusion of Huldah’s name on the gates of Herod’s temple may indicate that Jews during the second temple period shared a similar attitude towards women’s spiritual abilities. In fact, in the New Testament we see evidence that the Jews believed that women had access to divine communication and could speak prophetically, independent of a man. The gospel writer Luke tells us about a woman named Anna, who is described as “a prophetess” and lived within the temple complex. As Luke writes she, “departed not from the temple, but served God with fastings and prayers night and day.”[16] Anna was one of the first people to see baby Jesus when his parents brought him to the temple for the first time and was the first woman to declare Jesus as the Messiah. Furthermore, Anna shared her prophecy with, as Luke writes, “all of them that looked for redemption in Jerusalem.”[17] Just like Huldah, Anna was recognized by others in Jerusalem for her prophetic gift, was able to independently receive divine communication, and her words were taken seriously by some people in Jerusalem. In the time of the second temple a woman could still be a prophetess; gender was no barrier to receiving divine revelation.

Wife of Shallum

Huldah is also described as the wife of Shallum, who was the “keeper of the wardrobe.” What just exactly this phrase means, and what type of job or position it refers to is unknown. According to the BDB the Hebrew word בֶּגֶד, usually translated as “wardrobe,” refers to “garment, clothing, raiment, robe of any kind, from the filthy clothing of the leper to the holy robes of the high priest, the simplest covering of the poor as well as the costly raiment of the rich and noble.”[18] It has been speculated that Shallum could have been the keeper, or guard, of the priestly wardrobe.[19] The vestments worn by the priest and high priest had gemstones set in them, and it is possible that they required someone to “guard” them or to “keep” them clean and organized. It has also been suggested that Shallum could have been in charge of the royal wardrobe worn by the king and his family.

Regardless of what his job entailed, this detail about Huldah’s husband informs us that she occupied a well-respected, prestigious position within Jerusalem. Not only is she a married woman, a position that naturally brought with it respectability, but she was also the wife of a man with an important job. This is in contrast with the story of the “witch” of Endor told in 1 Samuel 28, which is the only other story in the Bible (besides Huldah’s) where a king consults a woman for divine revelation. This woman is consulted by King Saul after the Lord stops answering him through dreams, prophets and the Urim. Saul goes to her in secret, and she divines for him through a “familiar spirit.” In contrast, Josiah tells his men to “go enquire of the Lord” and their natural response to this command was to go to Huldah. There is no pretense at secrecy or hesitancy on their part to consult her, and Huldah responds to their enquires with the traditional prophetic pattern of כֹּֽה־אָמַר יְהוָה “thus saith the Lord.” There are no questions about Huldah’s legitimacy, like there are in the story of the woman at Endor. She is treated in a way that shows she held a position of respect and acts in a way that shows she had authority.

Yet significantly, Huldah is the only prophet in the entire Bible (as of yet) who made a prophecy that did not come true. She, after declaring to Josiah’s men that “book of the law” did indeed contain the laws of God and that He would ‘bring evil” unto the people who had for forsaken those laws, told Josiah that he would be “gathered into thy grave in peace.[20] Elsewhere in the Bible this phrase implies that someone dies a natural, nonviolent death.[21] Yet not long after this prophecy Josiah was killed in battle in Megiddo, which seems to be in direct violation of Huldah’s prophecy.[22] It would make sense that this blatant mistake would undermine Huldah’s credibility. Yet this knowledge, which the Biblical author obviously has, seems to make no difference in his opinion of Huldah or the validity of her prophecies.[23] Huldah is seen as a legitimate prophet.

In addition, at a time when many Judeans were tied up in the idolatrous worship of Baal, Asherah, and other ancient near eastern gods, Huldah was devoted to the worship of Yahweh. In fact, Huldah’s declaration that the “book of the law” found in the temple was true, was responsible for much of Josiah’s religious reforms. It was her prophetic declaration that spurred Josiah to purge the temple of all the “vessels that were made for Baal,” the Asherah tree and all other idolatrous objects.[24] He also broke down the “high places” all throughout Judah and consolidated all worship to only one main source, the temple in Jerusalem. [25] Before Josiah’s reforms it appears that worship and sacrifices were offered at other altars or “high places” outside of the temple. After his reforms the only authorized and acceptable place to worship and offer sacrifices was at the temple in Jerusalem. Huldah’s prophetic declaration was the impetus for a huge religious reformation that dramatically changed the way that Jews worshiped.

These reforms lasted long beyond Josiah’s and Huldah’s time and during the time of the second temple Jews were required to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem during religious festivals. The temple in Jerusalem was still the only place that sacrifices could be appropriately offered to Yahweh. Even today, Jews believe that no sacrifice or cultic worship can be performed outside the temple (which no longer exists). This belief in the exclusivity of the temple can be traced back to Huldah and her prophetic interpretation that inspired Josiah’s reformation. Huldah’s name, memorialized on the temple gates, stands as a reminder to all pilgrims– male and female– that it was a woman who helped to restore the correct form of worship; a reminder that women could speak and act with authority.

The Mishneh

The last detail we learn about Huldah is that she “dwelt in Jerusalem in the mishneh.” The meaning of the Hebrew word mishneh is not completely clear. In the Septuagint the word is translated as μασενα “masena,” simply a transliteration of the Hebrew. The Vulgate translates it as secunda, which means “the second,” and the Aramaic Targum translates it as בְּבֵית אוּלְפָנָא which means “study hall,” a place where the Torah is studied.[26] According to Rabbinical teachings the mishneh was a place where Huldah ran a school for teaching women the Torah in Jerusalem.[27] This interpretation is what probably led the KJV translation to render mishneh as “college” and has given way to many legends and stories about Huldah being a teacher or an academic.[28]

Yet when the word mishneh is used in other places in the Bible it means “double, copy, second.”[29] The prophet Zephaniah, who was contemporary with Huldah, mentions the mishneh as being a section of Jerusalem. He wrote, “And it shall come to pass in that day, saith the LORD, that there shall be the noise of a cry from the fish gate, and an howling from the second (mishneh), and a great crashing from the hills.”[30] Most newer translations of the Bible translate this word as “the second quarter,” meaning that it refers to a newer, “second part” of Jerusalem.

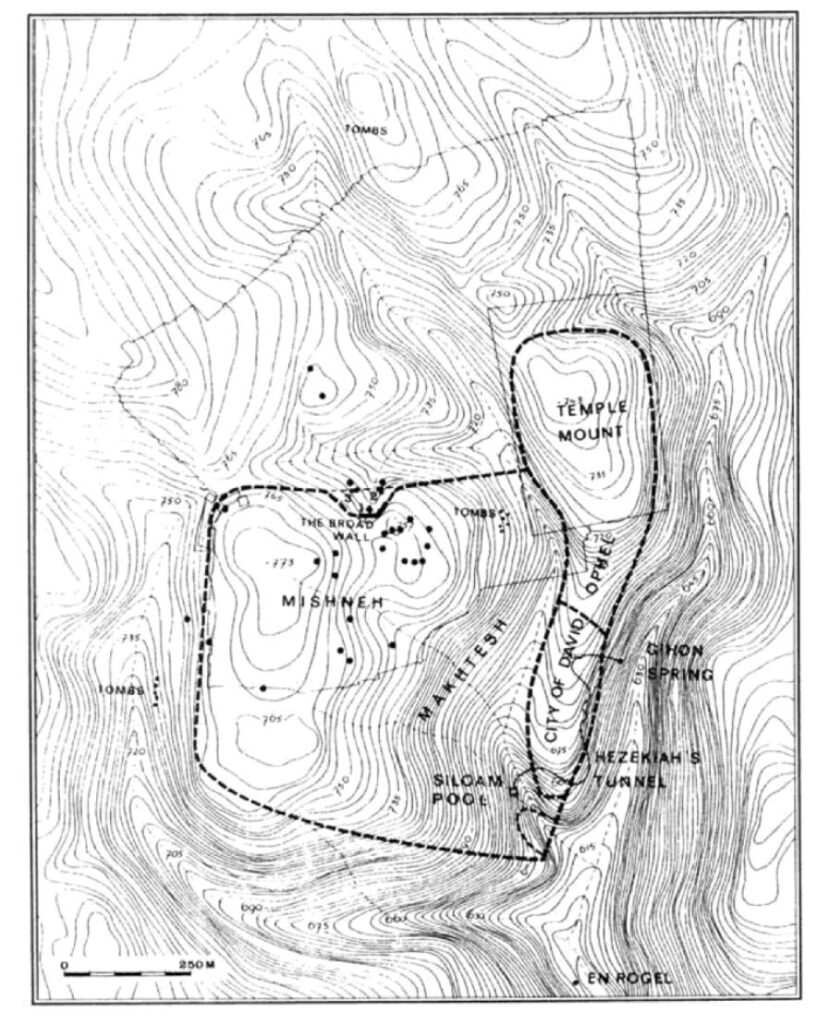

Today many scholars believe that the mishneh refers to an expansion or “second ” part of the city that was constructed in the 8th Century BCE to accommodate Jerusalem’s massive population growth.[31] Many scholars attribute Jerusalem’s growth in this time period to the destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel by the Assyrians in 722 BCE. The influx of refugees from Israel into Jerusalem may have necessitated the expansion of the city, or the city’s growth could have been a natural consequence of the prosperity and economic security of the region.[32]

The exact area of the mishneh is unknown but many archeologists believe that the mishnehwas the southwestern part of the city, which today houses much of the Jewish Quarter in the Old City. The remains of a second temple period wall have even been found in this area, and it appears that a “second wall” was constructed that would have extended west from the original City of David, encircled the top of the hill bordering the Hinnom valley, and then connected to the walls of the temple in the North.[33] This addition to the city would have more than tripled the original size of Jerusalem.

Still, regardless of where or what the mishneh was, the most intriguing question is why the Biblical author includes this detail about Huldah living in the mishneh in his account of her story. Why did he feel like this information was important? If the mishneh refers to a specific area of the city, the Biblical author may have been trying to explain something important about Huldah’s social status or tribal heritage. Archaeologists believe that the wealthiest part of Jerusalem in the second temple period would have been the original City of David area on the southwestern slope of the city. This is where the king’s palace would probably have been located and where the wealthy would have had ancestral homes and property.[35] In contrast, the mishneh, the “second” additional part of Jerusalem would have most likely housed the newcomers to Jerusalem; those whose families were not as established. It is possible that many of the residents of the mishneh may have been refugees from the northern tribes of Israel. Perhaps Huldah fell into this category.

If, as the Rabbis suggested, the mishneh refers to a place of study it makes sense that the Biblical author would tell us about it. Having a woman formally teaching the Torah would not only be a unique and memorable thing, but it also would have been specific. In this interpretation the mishneh may have been that name of the school or organization that Huldah was associated with. Rashi, in his commentary on 2 Chronicles 34:22 mentions that Jerusalem had two walls and that Huldah’s chamber, or school, was located between them. Rashi wrote:

“The city had two walls, and she lived between the two walls. The Targum renders: in the study-hall. The meaning is: in the place of Torah, for Huldah had a chamber adjacent to the Chamber of Hewn Stone. The Chamber of Huldah was open to the outside and closed toward the Sanhedrin in the Chamber of Hewn Stone. So it is written in Tractate Middoth (unknown) because of modesty.[36]”

Perhaps the Biblical author mentioned the mishneh because it was the specific place that Josiah’s men went to find Huldah in order to ask her their question. Some scholars have even speculated that the Huldah Gates were thus named because they were built in the area where Huldah’s school– the mishneh– was located.

Even though we know that there were men in the Second Temple period who did not believe in educating women, we do have evidence that some Jewish women learned the Torah and taught it to others. In the New Testament we hear about a Jewish woman named Eunice living in Lystra (part of modern-day Turkey) who was married to a Gentile man. Since it was a man’s responsibility to teach his son the Torah we would expect Eunice’s son, Timothy, to be uneducated in the scriptures. Yet, in 2 Timothy 3:15 the Christian apostle Paul writes, “that from a child thou [Timothy] hast known the holy scriptures.” We can infer that it was Eunice who taught her son the Jewish scriptures. She may not have been able to read or even had access to physical copies of the scriptures, but using what she knew, and had access to, Eunice was able to instruct her son. Perhaps like Huldah did, Eunice also taught others (even if it was just her children) the Torah.

It is fascinating to think about how Huldah’s name being associated with the gates of the temple might have influenced Jewish beliefs about women’s intellectual and spiritual capacities. If Huldah, the revered prophetess, had been an educated woman, a woman who taught the scriptures, and a woman to whom others looked to for answers, then it is possible that Jews of the second temple may have viewed women as capable of possessing those same abilities. Jewish women, on their way to the temple, may have passed right by the area of the mishneh and been reminded that they too could possess knowledge– from God and from the scriptures.

Conclusion

We have no tangible way of knowing or measuring the impact that the Huldah Gates had on the Jews on the second temple, but we can’t ignore the fact that, out of all the gates of Jerusalem only these gates–the most magnificent and monumental entrances to the temple– were named after a woman. The significance of that cannot be overlooked. The fact that the Huldah Gates were not a small, insignificant entrance, cramped somewhere in the back of the temple complex, but rather the huge, magnificent entrance to the temple must have had an impact on how the Jews felt about Huldah, and subsequently how they felt about women and women’s religious gifts. A feeling that women were important and valued would have been brought to the forefront of every pilgrim’s mind as they approached the temple through the Huldah Gates.

For young Jewish men having Huldah’s name prominently upheld would be a reminder that even a king sought out the counsel and advice of a woman. Perhaps remembering Huldah’s story inspired more than one man to listen to or consult with the women in his life. For a Jewish woman Huldah’s name emblazoned on the gates would have been a powerful reminder to her of a woman’s value within religion and of her potential for divine communication. Perhaps more than one woman was inspired by Huldah’s story to seek her own prophecy or to speak with authority before men. If anything, having beautiful, magnificent gates named after a woman would have given Jewish women a sense of worth and value.

The Huldah Gates are still one of the most magnificent remains of the Second Temple that exist. They bear testimony to the grandeur of the temple and its historic architecture. It is still possible, when standing on the remains of the monumental stairs leading up to the Huldah Gates, to feel the feeling of “ascending” to the temple and the climb to something more holy. The Huldah Gates can still inspire us, just like they may have the ancient Jewish pilgrims. Not only with respect and reverence for the temple, but also as a reminder that women possess powerful spiritual abilities.

There is a need today to rekindle a new respect and appreciation for Huldah’s story. To not only see her routinely included in religious teachings, in materials for children, in books about the Bible, but to value and appreciate the message of her story. To remember that at one time women were able to speak and act with authority, that gender was no barrier to communicating directly with God, and that women could be teachers and interpreters of scripture. These are all things that, in some religious circles, are outside the allowed sphere of women’s religious participation. Yet Huldah’s story suggests that women have had, and still do have, the spiritual capacity and permission to be prophetesses– to receive divine communication from God and share it with others.

More than two thousand years after they were first built, the Huldah Gates still stand as a reminder of the impact of Huldah and her prophecy.

Bibliography

Baruch, Y. and Reich, R. (2016). Excavations near the Triple Gate of the Temple Mount, Jerusalem. ATIQOT, 85, pp. 37–95.

Brown, Francis. (1996). The Brown, Driver, Briggs Hebrew and English lexicon: with an appendix containing the Biblical Aramaic: coded with the numbering system from Strong’s Exhaustive concordance of the Bible. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers.

Handy, L. K. (2010). Reading Huldah as Being a Woman. Biblical Research, 55, 5–44.

Hamori, Esther. (2013). The Prophet and the Necromancer: Women’s Divination for Kings. Journal of Biblical Literature, 132 (4), 827-843.

Geva, H. (2003). Western Jerusalem in the End of the First Temple Period in Light of Excavations in the Jewish Quarter. Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period, edited by Andrew G. Vaughn and Ann E. Killebrew. Society of Biblical Literature: Atlanta.

Kadari, T. (1999). Huldah, the Prophet: Midrash and Aggadah. In Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. Jewish Women’s Archive. Accessed https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/huldah-prophet-midrash-and-aggadah

McKinlay, J. (2011). Gazing at Huldah. The Bible and Critical Theory, 1 (3).

Mishnah: Six Orders. Edited by Chanoch Albeck. Jerusalem: Bialik, 1955–1959.

Na’aman, Nadav (2011), The “Discovered Book” and the Legitimation of Josiah’s Reform. Journal of Biblical Literature, 130 (1), 47-62.

Rashi. Chronicles, English translation by I.W. Slotki, Soncino Press, 1952

Reich, R. and Shukron, E. (2003). The Urban Development of Jerusalem in the Late 8th Century B.C.E. in Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period, edited by Andrew G. Vaughn and Ann E. Killebrew. Society of Biblical Literature: Atlanta.

Regev, E. (2005). The Ritual Baths Near the Temple Mount and Extra-Purification Before Entering the Temple Courts. Israel Exploration Journal, 55 (2), 194–204.

Scheuer, B. (2017). Animal Names for Hebrew Bible Female Prophets. Literature and Theology, 31 (4), 455–471.

Scheuer, B. (2015). “Huldah: A Cunning Career Woman?”. In Prophecy and Prophets in Stories. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

The Tosefta. Edited by Saul Lieberman. 5 volumes. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1955–1988

[1] Middot 1:3 it records that, “There were five gates to the Temple Mount: The two Huldah gates on the south were used both for entrance and exit; The Kiponus gate on the west was used both for entrance and exit. The Taddi gate on the north was not used at all. The Eastern gate over which was a representation of the palace of Shushan and through which the high priest who burned the red heifer and all who assisted with it would go out to the Mount of Olives.” See Mishnah: Six Orders. Edited by Chanoch Albeck. Jerusalem: Bialik, 1955–1959.

[2] In the Mishnah [Middoth 2:2] it records that if a pilgrim was in mourning that they would enter and exit at the opposite gates, walking against the flow of traffic, so that people would know of their grief and offer them comfort. See Mishnah: Six Orders. Edited by Chanoch Albeck. Jerusalem: Bialik, 1955–1959.

[3] Bava Batra 1:11 and Negaim 6:2 in The Tosefta. Edited by Saul Lieberman. 5 volumes. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1955–1988

[4] Na’aman, Nadav (2011), The “Discovered Book” and the Legitimation of Josiah’s Reform. Journal of Biblical Literature, 130 (1), 47-62.

[5] Several prominent models of Jerusalem during the second Temple period, including the large 3D one at the Israel Museum, include a depiction of Huldah’s tomb outside the Huldah Gates of the temple.

[6] Baruch, Y. and Reich, R. (2016). Excavations near the Triple Gate of the Temple Mount, Jerusalem. ATIQOT, 85, pp. 37–95. Also, since Huldah lived during the first temple period it is unlikely that the gates of the first temple bore her name. In fact Nehemiah, a prophet who lived after the destruction of the first temple and who helped rebuild Jerusalem in the mid-5th century, gave us the names of all ten gates of Jerusalem that the returning Jews reconstructed: Sheep Gate, Fish Gate, Old Gate, Valley Gate, Dung Gate, Fountain Gate, Water Gate, Horse Gate, East Gate, and Inspection Gate. It is possible that the southernmost gate, in Nehemiah’s day “Water Gate” later became associated with Huldah, because of the association with her tomb.

[7] Some Jews Pilgrims to Jerusalem in the Middle Ages wrote that they had visited the tomb of Huldah located on the Mount of Olives. Some believe that, while Huldah’s tomb was originally outside the gates of the temple, it was (at some point) moved to the Mount of Olives. Today, there is a tomb on the Mount of Olives that some Jews claim to be the tomb of Huldah. Yet interestingly both Muslims and Christians also claim that the same tomb is the burial place for pious women from their religions. Muslims believe that is the tomb of a woman named Sit’ Raba’a al-Aduwiyyeh who, according to Islamic tradition, was a great mystic in the 7th century who wrote beautiful poetry. Christians believe it to be the tomb of St. Pelagia, an actress and singer from Antioch in the 5th century, who left her sinful life behind her when she converted to Christianity. She was said to have lived in a monastic cell in Jerusalem, living a life of piety and prayer. Yet, regardless of who was actually buried there, the tomb is associated by all three religions with women of spiritual power and purity.

[8] Handy, L. K. (2010). Reading Huldah as Being a Woman. Biblical Research, 55, 5–44.

[9] Ibid.

[10] This may be in part because in Hebrew the name Huldah means “weasel,” and thus is not an attractive baby name.

[11] 2 Kings 22:14 KJV

[12] The inclusion of the definite article הַ “the” in front of the word prophetess in the description of Huldah is also an important detail of her story. She is not just described as “a prophetess” like Deborah is in Judges 4, but as “the prophetess” indicating that she was somehow unique.# Perhaps the definite article here indicates that there was just one prophetess in Israel and that she was it, or that Huldah was considered to be “the” authoritative, chosen prophetess among other prophetesses within Judah. Either way her title of “the prophetess” designates as being accepted and established.

[13] Scheuer, B. (2017). Animal Names for Hebrew Bible Female Prophets. Literature and Theology, 31 (4), 455–471.

[14] In writing about Josephus’ description of Huldah, which was written for a Hellenistic audience, Handy explained: “Josephus’ emphasis of Huldah’s female gender would not have negatively affected the trustworthiness of her message and may have well been intended to enhance Huldah’s reception by a Roman audience familiar was they were that Delphi’s prophetess was the single most authoritative source for the very words of a deity. Josephus’ emphasis on Huldah’s gender would especially ring true at a time when there was some concern about the decrease in Delphic messages and an interest in acquiring ever more and ever more distant exotic oracles.” See Handy, L. K. (2010). Reading Huldah as Being a Woman. Biblical Research, 55, 5–44.

[15] The Talmud says she was a relative of Jeremiah, the Midrash says it was her husband who was pious and thus rewarded with a wife with a prophetic gift, the Megillah (14b) argues that it was because a woman would be more merciful than a man that Josiah went to Huldah.

[16] Luke 2: 37 KJV

[17] Luke 2: 38 KJV

[18] Brown, Francis. (1996). The Brown, Driver, Briggs Hebrew and English lexicon: with an appendix containing the Biblical Aramaic: coded with the numbering system from Strong’s Exhaustive concordance of the Bible. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers.

[19] Scheuer, B. (2015). “Huldah: A Cunning Career Woman?”. In Prophecy and Prophets in Stories. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

[20] 2 Kings 22:20

[21] See 1 Kings 2:6

[22] 2 Kings 23:29-30

[23] Interestingly the account in II Chronicles 35: 20-24 of Josiah’s death tells the story differently, in a way that might preserve Huldah’s credibility as a prophet. In Chronicles it is Josiah who initiates the conflict between him and the Pharaoh in Megiddo. The Pharaoh responds by sending ambassadors to Josiah who warn him to not make war with him because he had been commanded by God to “make haste.” He tells Josiah, “Forbear thee from meddling with God, who is with me, that he destroy you not.” The Chronicler then tells us that Josiah did not “hearkened not unto the words of Necho from the mouth of God.” He continued the attack and was killed in battle. In this version of the story the prophecy of Huldah is negated by the fact that Josiah sins, he refuses to listen to the word of God that came through Necho (who as a king would be acknowledged as having the divine right to receive revelation). The Chronicler’s story seems to shift the blame on Huldah’s failed prophecy to Josiah, making him responsible for losing God’s blessing and protection. See Hamori, Esther. (2013). The Prophet and the Necromancer: Women’s Divination for Kings. Journal of Biblical Literature, 132 (4), 827-843.

[24] 2 Kings 23:4 KJV

[25] 2 Kings 23:5 KJV

[26] See the Targum Jonathan on II Kings

[27] Pesiqta Rabbati 26:129 mentions Huldah had a school for women while Jeremiah had one for men in Jerusalem.

[28] Many accounts of Huldah describe her as a learned woman, who could read ancient languages, but it is important to note that there is no mention of Huldah actually reading the book of the law. It is possible that, like a Greek Oracle or a Mesopotamian prophetess, Huldah could have been consulted for her ability to discern the truth or commune with god in order to know the validity of the book. The idea that the book must be read, or the language analyzed, in order to be validated is a more modern mindset. An ancient attitude towards finding truth would have been much different, and probably much less academic.

[29]Brown, Francis. (1996). The Brown, Driver, Briggs Hebrew and English lexicon: with an appendix containing the Biblical Aramaic : coded with the numbering system from Strong’s Exhaustive concordance of the Bible. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers.

[30] Zeph. 1:10 KJV

[31] Geva, H. (2003). Western Jerusalem in the End of the First Temple Period in Light of Excavations in the Jewish Quarter. Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period, edited by Andrew G. Vaughn and Ann E. Killebrew. Society of Biblical Literature: Atlanta.

[32] Reich, R. and Shukron, E. (2003). The Urban Development of Jerusalem in the Late 8th Century B.C.E. in Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period, edited by Andrew G. Vaughn and Ann E. Killebrew. Society of Biblical Literature: Atlanta.

[33] Geva, H. (2003). Western Jerusalem in the End of the First Temple Period in Light of Excavations in the Jewish Quarter. Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period, edited by Andrew G. Vaughn and Ann E. Killebrew. Society of Biblical Literature: Atlanta.

[34] Geva, H. (2003). Western Jerusalem in the End of the First Temple Period in Light of Excavations in the Jewish Quarter. Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period, edited by Andrew G. Vaughn and Ann E. Killebrew. Society of Biblical Literature: Atlanta.

[35] Geva, H. (2003). Western Jerusalem in the End of the First Temple Period in Light of Excavations in the Jewish Quarter. Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period, edited by Andrew G. Vaughn and Ann E. Killebrew. Society of Biblical Literature: Atlanta.

[36] Rashi. Chronicles, English translation by I.W. Slotki, Soncino Press, 1952